Combe St Nicholas Today

The Parish of Combe St Nicholas lies about 2 miles from Chard and 10 miles from Taunton; it is almost 4800 acres in area and the boundary length is just under 14 miles. This “hollow in the hills” (or ‘cwym’, from the Gaelic, spoken by the Celts of Cornwall and Wales) is set in lovely countryside on the edge of the Blackdown’s, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

The Parish of Combe St Nicholas lies about 2 miles from Chard and 10 miles from Taunton; it is almost 4800 acres in area and the boundary length is just under 14 miles. This “hollow in the hills” (or ‘cwym’, from the Gaelic, spoken by the Celts of Cornwall and Wales) is set in lovely countryside on the edge of the Blackdown’s, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.

Evidence of prehistoric occupation dating back to around 1400 BC has been found at Combe Beacon, and there was a significant Roman presence, with Roman villas at Wadeford and Whitestaunton and a Roman mill at Wadeford. The parish came into the possession of Aelfthryth, the first English queen, and in the 11th century, was bought by the Bishop of Bath, who used income from it to help pay for the building of Wells Cathedral. Previously known as Combe Episcopi, the village took its present name when the church was dedicated to St Nicholas in 1239. Sheep, wool and wool trades were important, and the wealth of springs allowed 4 mills (two grist and two box cloth) to operate at one time, as well as a brush factory at Nimmer. The Green Dragon pub has been in existence since 1611.

The current parish has a primary school, a village hall, a village shop incorporating post office services, a farm shop, a hairdresser, 2 pubs, a garden centre, a plant nursery, a small factory, village allotments and a football ground. A wide range of social activities takes place with various groups catering for general or specific interests. From the 2011 census, the population was 1373 people of which 430 were over 65 years old.

Introduction to our Parish History

The basis for this history was taken from an account of the History of Combe St. Nicholas by the Rev. Geoffrey de Y. Aldridge shown in the Proceedings of the Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society for the Year 1927 – Vol.LXX111. The Rev. Aldridge was Vicar of Combe from 1917 to 1942.

Prehistoric

Combe St. Nicholas has been inhabited from very early times. The work “Combe” means “valley” in Celtic languages and was probably given to the valley of the River Isle by the Iron Age Celts who lived here.

Combe St. Nicholas has been inhabited from very early times. The work “Combe” means “valley” in Celtic languages and was probably given to the valley of the River Isle by the Iron Age Celts who lived here.

The introduction of farming from about 4000BC saw major changes in the appearance of the area with large-scale deforestation being reflected in the pollen record. Over the next 2000 years more than half of the original woodland had been cleared. Signs of Neolithic activity on the landscape of western Somerset and eastern Devon are sparse. The nearest possible causewayed enclosures to Combe St. Nicholas are on Ham Hill near Ilchester and Hembury Hill near Honiton. A possible ploughed out long barrow within Combe St. Nicholas is suggested by the lane called Giants Grave Road running along the spur between the River Yarty and a tributary, but there is no visible evidence.

The Bronze Age has left at least one definite monument in the landscape of Combe St. Nicholas; a bell barrow on Combe Beacon the highest point of the Blackdown ridge about 1km NW of the village of Combe. It is located on the Taunton/Chard road near to the junction with the hill leading down to Combe. This barrow, built in about 1000BC, has commanding views over all the surrounding region and particularly to the east where the Somerset Levels and Mendip are easily visible. The barrow was excavated in 1935 and a funery urn filled with ashes was found. This barrow is one of a group of about 20 on the Blackdown Hills. Two others of these can be found at Northay about 2km west of Combe. The site does appear to have been used as the site of a beacon. An OS trig point is located on top of the barrow. See the report on the landscape of Combe.

It is possible that the ridges of the Blackdown Hills were used as communication routes throughout the prehistoric period. Such a ridgeway track has been postulated to run north from the North Dorset Ridgeway , west of where Chard now stands, past the barrow on Beacon Hill to Neroche and then west along the Blackdown Ridgeway. See the report on the Roads of Chard.

There is no evidence of Iron Age occupation in Combe, but the surrounding area contains several sites which might be of this period .For example two enclosures are located south of Howley 4km west of Combe. Combe St. Nicholas is just outside the area of great hill forts which cover the territory of the Durotriges to the east The nearest of these, clearly visible from many points in Combe St. Nicholas, is on Ham Hill near Ilchester. Closer at hand however is the smaller hill fort at Neroche on the site of the later Norman castle.

Based upon the evidence of the distribution of coins it is suggested that Combe St. Nicholas lay close to the boundary between the territory of the Durotriges to the east and the Dumnonii to the west. This boundary was probably maintained by the Romans when establishing their ‘civitates’, or settlements. To the east of Combe St. Nicholas is a region with many highly Romanised buildings with a cluster of villas around Ilchester and a string of them at approximately 1km intervals along the Fosse Way from Ilchester to Dinnington a few kilometres east of Combe St. Nicholas.

Romans

West of Dinnington are the Romanised sites at Wadeford , South Chard and Whitestaunton. These are amongst the most westerly Romanised sites in England . Once again the Dumnonii to their east do not seem to have accepted ‘modern’ innovations.

There are no confirmed Roman roads in or near Combe St Nicholas except for the Fosse Way which runs to the south of Chard. One source has stated that a road ran west from Dinnington to the Chard area and then roughly followed today’s A30 to Exeter. There are no obvious visible signs of such a road but it would run much closer to the Wadeford and Whitestaunton sites than the Fosse Way. The Somerset Sites and Monuments Records also suggests that part of the ridgeway close to Combe Beacon was Romanised , with a possible ‘agger’, or embankment, visible running parallel to the modern road.

The Roman, or more probably RomanoBritish, site at Wadeford, has the remains of what must have been an unusually fine villa, the residence of a man of wealth and culture. It is located in a field on the right hand site on the road to Scrapton from Wadeford. The site has never been thoroughly explored, but the remains which have been uncovered from time to time, point to a house of the courtyard type. It was first discovered in 1810, when two fine mosaic pavements were unearthed. One, measuring 6 feet by 8 feet, showed a geometrical pattern of conventional flowers in circles and octagons in yellow, red, blue and grey on a white ground, the whole being set in a border of plain red brick tessellation. The other pavement, 6 feet square, consisted of a central circular panel enclosed in two interlacing squares, which in their turn were contained by an octagon, while a square of meander pattern bordered the whole. Both these mosaics perished soon after 1810 through frost. In 1861 some excavations were made revealing five more pavements and a hypocaust. Other finds included tiles, painted wall plaster, roof slates, a bronze hand, a ring fibula, and coins. Evidence of Roman industry have been found at Court Mill, Wadeford, showing that the mill was worked in those early times, while in 1858 five Constantinian coins were found in the churchyard, pointing perhaps to a very early association of this site with religious observances.

Further details concerning the Villa can be seen in a 1903 description of the site.

Saxons

When the Roman field army was withdrawn and pay for the rest ceased the Roman economy collapsed but presumably the local landowners and population continued to live off the land. In Dumnonia which had never really been Romanised the differences may not have been significant except that taxes ended up with a local leader rather than going to a central coffer. There may have been some population reduction and some areas, such as the Somerset Levels fell out of production due to flooding or failure of the drainage systems but in general agricultural life would have continued. Somerset and further west was largely sheltered from early Saxon raiding. The Saxon takeover was delayed until over 250 years after the Roman departure and when it did occur was gradual. The area around Bath is claimed by the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to have been conquered in AD577, the River Parrett to be reached 80 years later in AD658 and Eastern Devon only in AD682. This process is unlikely to have been accompanied by a major change in land organisation and is more likely to have been achieved largely by a change of lordship similar to that of the Normans 400 years later. There is thus every possibility that estate boundaries of the Saxon periods had their origins in the Roman period or earlier.

The first documentary source relating, even if indirectly, to Combe St. Nicholas is a charter recording the grant, around AD700 of 20 hides at Ilminster by Ynys, king of the West Saxons, to the monastery of Muchelney. M. Costen ( 1988,33) believes that the charter is genuinely of 8th century date and thus it describes a situation within a few decades of the Saxon takeover. The estate defined coincides with the modern (pre 1980s) parish of Ilminster and thus also includes the ‘bite’ into the east side of Combe St. Nicholas where the two parishes meet. The relevant section reads, “ From Watercress Ford (Carsford) to Whiteway (Wite Wey) then by the Hillfoot (Wyrcrume) to the Steep Uphill Path (Sticklepathe) then to Stone……. (Stoneberninge). From Stone……… to Donyatt (Dunnegete)”.

Chilworthy House, previously outside of Combe parish, was mentioned in the Saxon Charter of Ilminster of 725.

Combe had its associations with royalty and was the residence, and one of the manors, of Aelfthryth, daughter of Ordgar, Earl of the Western Provinces, and widow of King Edgar. A letter is extant written by her to Archbishop Aelfric (995-1005) in which she says:

“I Aelfthryth greet Archbishop Aelfric and Earl Aethelweard humbly, and I make known to you that I am witness that Archbishop Dunstan [960-988] assigned Taunton to Bishop Aethelwold [Bishop of Winchester 963-984] as his charters declared, and King Edgar then gave it up and commanded each of his thanes who had any land in that land that they should hold it with the bishop’s consent or give it up, and the king said that he had no land to give out as he durst not from fear of God have the headship himself and moreover had then surrendered Rushton into the bishop’s hands. And Wulfgyth then rode to me at Combe and sought me, and I then, because she was akin to me, and Aelfswith, because he was her brother, obtained from Bishop Aethelwold that they might enjoy the land for their day, and that after their day the land should go to Taunton with meat and with men as it stood’.

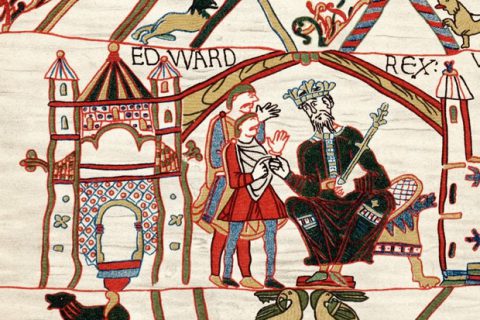

Later the manor passed into the hands of one Azor, son of Torold, a courtier of Edward the Confessor.

The Normans

The Normans

Following the invasion of 1066 the area was probably controlled by the Normans from a castle built at what is now known as Castle Neroche, about 5 miles from Combe on the Taunton road. Recent excavations indicate that the site was firstly an Iron Age fort and later used by the Saxons. The Normans took the fort in 1067 and built a motte and bailey castle. The fort was taken by William the Conqueror’s half brother, Count Robert of Mortain but he abandoned it in 1087 and moved to Montacute fifteen miles to the east.

By the time of the Domesday survey large areas of Somerset were ecclesiastical estates. In the SW of the county the bishop of Wells held much of the land including Chard and Combe St. Nicholas while Muchelney Abbey held Ilminster.

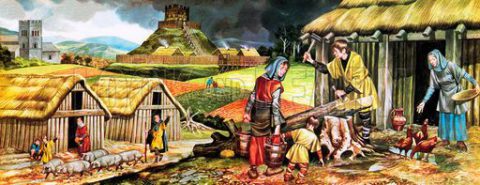

The Doomsday Survey (1086) says of Combe: ‘The same Bishop (Giso) holds Combe. Azor, son of Torold, held it in the time of King Edward and paid geld for 20 hides. There is land for 16 ploughs. Of this (land) there are in demesne 8 hides where are 3 ploughs and 12 serfs and (there are) 15 villeins and 13 Borders with 12 ploughs and 12 hides. There are 12 beasts and 18 swine and 315 sheep and 1 riding horse. There are 12 acres of meadow and half a league of pasture reckoning (inter) length and breadth, and 1 league of woodland reckoning length and breadth. It was worth 10 pounds. Now 18 pounds.’

Combe was purchased in 1072 by Bishop Giso (1061-1088) as a part of the endowment of his cathedral church at Wells. Except for the duration of the Commonwealth it remained the property of the cathedral, though administered since 1839 by the Ecclesiastical Commission. An excellent description of the sale has been copied from the records of the Somersetshire Archaeological and Natural History Society. The principal witness to the sale was Edith of Wessex, the widow of Edward the Confessor. It took place at her home, Wilton Abbey, which was then a nunnery. According to one report, she had been exiled there by Edward in 1057.

Middle Ages

Middle Ages

The village is first mentioned in medieval documents, primarily in the context of Combe St Nicholas church, which was re-dedicated in 1239. The major manorial landholder in the parish was the Bishop of Wells; in 1234 local management was devolved to a Provost of the Cathedral, who had a residence in Combe St Nicholas village ‘on the north side of the road to Stanton’ (Whitestaunton). A courthouse and ‘mansion’ complex in Combe St Nicholas is well described in the Dean and Chapter court roll records from the 16th century as having “hall, kitchen, parlour, buttery, other necessary six rooms with divers chambers… with garden, backside and Court garden, with Barnes…… Court or Courtgreen of the same, dovehouse and culverhouse.” The 1813 estate map produced for the Dean and Chapter of Wells (plot numbers 1106-1110) confirms the site of the Court house, stables with “the great barn” in Combe St Nicholas village across the road from the church. All buildings have now been demolished.

It was probably that during the middle ages Combe began to be known as Combe Episcopi (this means Bishop’s Combe), a title which gradually fell into disuse after the dedication of the third church to St. Nicholas in 1239 by the Bishop of Waterford in the presence of Bishop Jocelin of Bath. . (See link to The Story of St. Nicholas) Evidence of the Norman churches remain with a pillar near the north porch, the lower part of the stonework of the chancel, the lower part of the tower and the tower door arch.Although a document of 1316 states that Combe Episcopi in the hundred of Kingsbury then belonged to the Dean and Chapter of Wells, and during the reign of Richard III, 1483-85, there may be a reference to Henry Bonner, owner of the ancient manor of Waterleston (now known as Weston) within the parish, and ‘Waterleston and Combe Episcopi’.

At some stage in the late medieval period the Weston estate became a separate manor. The settlement today comprises a farmstead and a deserted settlement site with an existing chapel, daughter chapel to the church at Combe. It is described in the Somerset Historic Environment Record as a possible medieval manorial complex. In fields adjacent to the chapel and the existing farmhouse there are earthworks suggesting building platforms, from which 12th to 14th century pottery has been identified. Documentary evidence also supports the presence of a hamlet during the 13th and 14th centuries. (Weston remained in the parish until the boundary changes of 1982)

It is probable that at the same time as he dedicated the new church at Combe, Bishop Jocelyne granted the charter for Combe Fair to be held on or about the Octave of the Feast of St. Nicholas (6th December). This fair was held for centuries on the Wednesday after 10th December in the streets opposite and adjacent to the church. It was a very important fair in bygone days, and was notable in that it was held in the early morning and most of the business was conducted by the light of lanterns. It finally expired towards the end of the 19th Century.

Under Bishop Reginald (1174-1191) the manor of Combe was assigned to the Precentor of Wells, (and from 1217 the provost,) subject to the payment of five prebends (a type of benefice which usually consisted of the income from the cathedral estates) in the Cathedral. But some forty years later the manor had apparently much increased in value, for in 1217 Bishop Jocelyne formed ten prebends out of the previous five, each to receive 10 marcs. One of these was appointed by the Bishop to be Provost of Combe; he had to pay the others, and he held, besides his own 10 marcs, the church of Combe.

In 1234 a further reorganisation of the Cathedral revenues was effected, and the Provostship of Combe, consisting of Combe manor and church, was united with the Provostship of Wynesham, consisting of Wynesham manor and church. And the Provost of Combe, was charged with the administration of fifteen prebends, retaining one for himself, and paying to each prebend 10 marcs. These fifteen prebends of Combe still exist in Wells Cathedral.

Maps

Click on the index below for the map you would like to enlarge.

Early 19th Century Map of the area

A Big Thank you goes to:

Thanks are due to Tony Dickinson for extracts from his report on the landscape of Combe; Mark McDermott for help with the chapter on the Middle Ages and with the history of the church; John Malcolm for the recollections of a Combe volunteer in 1798; letters from two Combe soldiers who fought in the second Boer War of 1899 to 1902, and details of the fire of 1883; Julie Hann of Cincinnati, USA, who provided information regarding the Rossiter family; Don Torrey, of Washington, USA, who sent details of the Torrey family; Randy Mardres of Virginia, USA, for details of the Marder family; Mrs. Dorothy Jones for useful additions for the 18th and 19th Chapters; Phillip Hoyland for details of the Combe and other Friendly Societies; Malcolm and Carolyn Butler for details of the history of Wadeford House and additional material regarding the Bethell family; Chris Duncan for details of Chilworthy House, theGenealogist.co.uk and the author, Brad Hepburn, for the 1844 story of Jane Pavey Cuff; Derrick Warren for extracts from his book Mills of the Isle; Chard History Group for the extract on roads from their publication “The Roads, Canal and Railways of Chard”; the Somerset Vernacular Building Research Group for the article on fulling and the cloth industry and additions to the Middle Ages chapter; Stanley Hopkins for details of the Methodist Church; the Somerset Archaeological and Natural History Society for extracts from their records; the staff of the Somerset Studies Library at Taunton;Somerset; Historical Environment Record; and Combe St. Nicholas History Group and parishioners for additional material.

References have been made in this history to the Parish Church, this is a separate document that can be accessed by clicking on the link. Other documents can be accessed by clicking on the blue links.

The Somerset Vernacular Building Research Group have undertaken a survey of traditional buildings in the parish. A book detailing their findings has been published and is available for purchase from the village post office or direct from the Group. The library now has some copies and information on the book is on the Group’s site at www.svbrg.org.uk